By: Ginger Christ and Ryan Golden

• Published March 11, 2025

Five years.

Five years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19, known then as the novel coronavirus, a global pandemic.

Five years since states and municipalities issued stay-at-home orders, and citizens were told to shelter in place.

Businesses around the country — and world — shut down. In the early days, movement was limited to essential workers — healthcare professionals, emergency responders and postal workers, among others. Companies scrambled to react.

Overnight, entire workforces went remote. Schools closed, and parents struggled to juggle working from home and caregiving. The unemployment rate skyrocketed as businesses scaled back or closed.

Work, as the world knew it, changed.

While the pace of change in human resources now certainly isn’t as furious as it was when the pandemic hit, dealing with disruption has always been a part of the profession, said Megan Berki, global people leader at Rocket Lawyer, a legal platform.

“I view it as the nature of HR,” she said. “There’s always going to be change that HR and organizations have to react to based on just the climate of the market and all kinds of different factors” — from the evolution of technology to skills training to responding to new legislation.

Remote work crawled, so flexibility could fly

Pew Research Center estimates about 40% of workers have jobs that can be done remotely, and huge swaths of these individuals did so during the onset of the pandemic. Zoom calls replaced in-person meetings; sweat pants replaced trousers; and commutes became a walk from the bedroom to the dining room table.

The huge shift to remote work fundamentally changed how companies managed employees, experts told HR Dive.

“Pre-COVID, in the office, there was a lot more in-person interaction, and a manager could observe much more directly how a person works and give feedback in real time. It was a much more fluid and engaging relationship,” Berki said.

With a suddenly remote workforce, employers had to reinvent how they coached, trained and engaged employees, she said.

“HR has had to get a lot more proactive, consistent and engaging,” Berki said.

Talent acquisition in a remote world also took on a new life. Companies were able to hire workers in locations where they didn’t have offices, opening up a larger talent pool.

“We expanded into markets that we probably otherwise wouldn’t have, outside of COVID and post-pandemic, because we were an office organization,” Berki said. “We had offices in very targeted locations, and when we moved to remote, it opened up other markets for us that I think [have] really benefited our workforce.”

Remote and flexible work opened up access for underrepresented employees. A recent report by Flexa found that record numbers of Black workers and employees with disabilities were looking for positions with flexible schedules last year.

As more employers announce return-to-office mandates, it is unlikely that the workplace of the pre-COVID era will return, experts say.

“I don’t think anybody has figured it out. I think there’s a number of people trying different things to see what sticks,” Berki said. “There’s always going to continue to be some degree of flexibility.”

From increased productivity to a more diverse workforce to a better work-life balance, the pros of remote work are evident, said Jessica Hardeman, Indeed’s global head of DEIB+ and talent attraction.

“We are in an era where we’re going to have to focus on flexibility, because we have seen the need [and] demand for it now,” Hardeman said. “The future is about continuing to be intentional and thoughtful about the flexibility that we’re preserving, because I think we lose out on really, really good talent when we choose to not be flexible.”

Now and in the hybrid future, ensuring there’s a good workplace dynamic and culture among dispersed teams will remain a top priority, Hardeman said.

“I trust that they’ll get their work done. I’m really focused on how I can make sure that they’re having a good experience as an employee,” she said.

Enter virtual Form I-9 review

With workforces spread across the country came a need to effectively document those workers.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Form I-9s, the documents used to verify that an employee is eligible to work in the U.S., had to be reviewed in person. But on March 20, 2020, the federal government temporarily permitted companies that were working completely remotely to review those documents virtually.

“Some of the changes we’ve seen relating to the I-9 process for COVID really were actually monumental,” said John Fay, director of product strategy at Equifax Workforce Solutions. “It's always been an in-person affair… Obviously, COVID came along, and that became, in many instances, a virtual impossibility.”

After several extensions and relaxed rules on the definition of a remote worker, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security issued a final rule in July 2023 that created permanent remote I-9 verification.

“It’s been a huge shift, and a lot of organizations are using it,” Fay said.

The documentation required by an employer remained the same, said Jorge Lopez, a Littler shareholder and chair of the law firm’s immigration and global mobility practice.

“It’s the mechanisms that’ve been put in place to meet the requirements that have been tweaked,” Lopez said.

But with any change come growing pains.

The virtual option allows companies to centralize the I-9 completion process, Fay said, but that benefit “can also be a potential weakness.” For companies with HR professionals across the country, shifting I-9 verification to the centralized team can burden what are usually small teams, he said.

That burden is amplified by the Trump administration’s plans to prioritize immigration enforcement, Fay said. Likewise, Lopez said to expect “a more robust enforcement environment in Trump world phase two.”

“When we think about immigration enforcement, some employers don’t necessarily equate it to I-9, but the I-9 is, in essence, an immigration form; it’s all about ensuring that employers hire a legal workforce,” Fay said. “Historically, when we have seen increases in immigration enforcement, we typically see an increase in the number of I-9 inspections.”

Some companies are opting to get out of the I-9 business altogether and are choosing to outsource the process, Fay said.

Religious accommodations claims rise

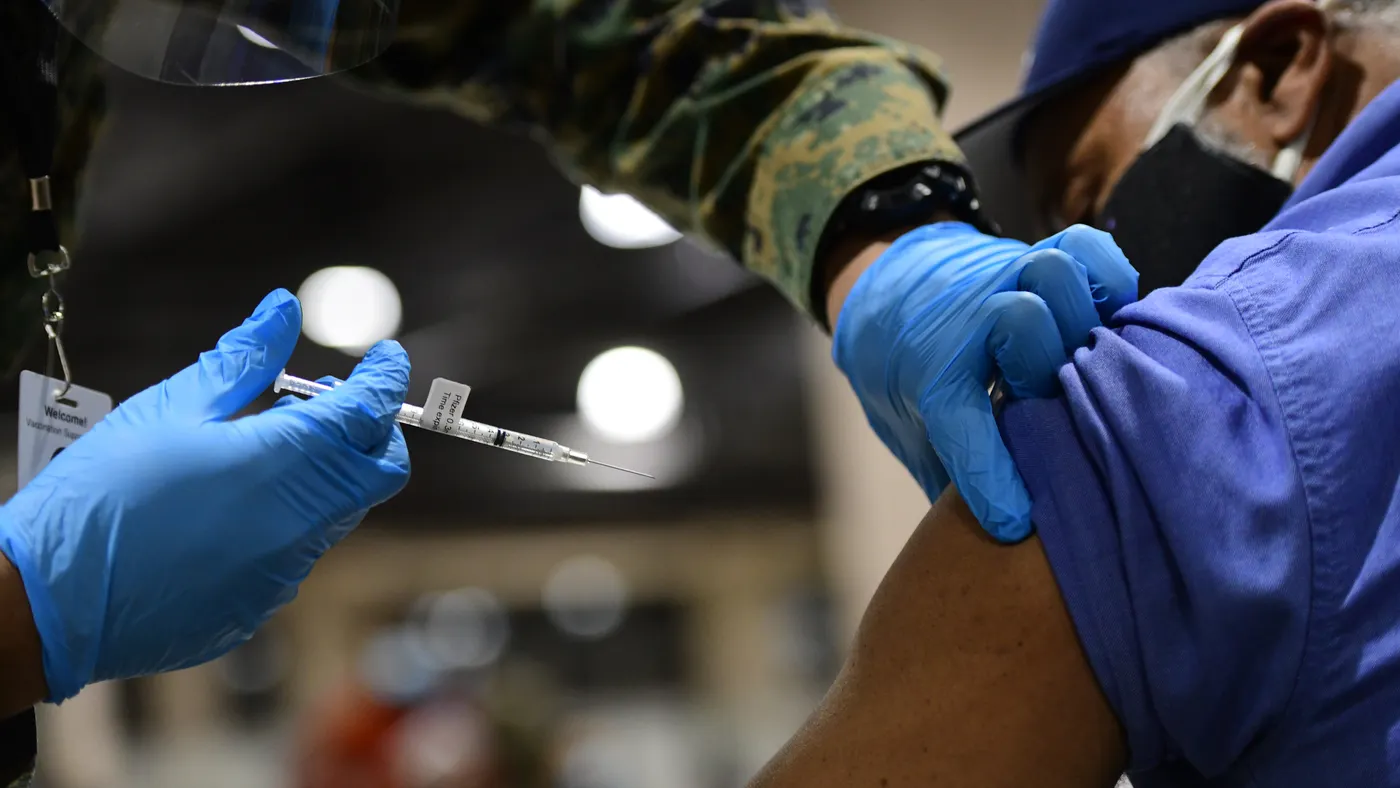

Few topics received as much public scrutiny over the course of the pandemic as vaccination requirements. As COVID-19 vaccines became more widely accessible, so too did the push from institutions — employers included — to mandate people receive them.

Federal authorities, including the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, generally signed off on policies requiring employees to submit proof of vaccination with some exceptions, including situations in which the employee would be unable to receive a vaccine due to a sincerely held religious practice or belief.

One of the downstream effects of such requirements, however, was an increased awareness among employees of their right to religious accommodations. HR Dive covered several lawsuits in which employees alleged that they had been illegally fired for requesting religious accommodation in lieu of receiving a COVID-19 vaccine.

In 2023, law firm Seyfarth Shaw found that religious discrimination claims filed with EEOC increased by over 600% year-over-year between the agency’s 2021 and 2022 fiscal years. Seyfarth Shaw said the increase appeared “almost entirely attributable” to the pandemic and accompanying vaccine mandates.

The link between COVID-19 vaccine mandates and religious accommodation requests is a real one, said Jonathan Segal, partner at Duane Morris. He noted that several websites and organizations began to offer education to people about their right to a religious accommodation, even in cases where an employee does not have a formal religion or where the employee’s particular religious belief is inconsistent with the religious organizations to which the employee belongs.

“There’s been an undeniable increase in the number of religious accommodation claims,” Segal said. “Vaccine mandates brought to the fore the idea of religious accommodations where people hadn’t thought about it before all that often,” Segal said.

The litigation that occurred as a result of this trend resulted in varying outcomes for employees filing lawsuits, some of whom had their cases dismissed and some of whom received favorable jury decisions requiring employers to compensate them for damages. But religious accommodations received even broader attention in the years since COVID-19, thanks in part to a landmark 2023 U.S. Supreme Court decision which made it harder for employers to deny an employee’s proposed religious accommodation due to undue hardship.

Segal said he still sees employers that neglect to focus on religion in the context of their anti-discrimination training. That presents a risk for employers, he added, particularly because it implies the lack of both a potential deterrent for bad conduct as well as a potential legal defense in the event of a lawsuit.

“There are myriad ways in which employers can discriminate without realizing that they’re doing it,” Segal said. “This is an opportunity for employers to take a look at their training practices, employment policies and complaint procedures and ensure that religious issues are covered.”

Article top image credit: Mark Makela via Getty Images