Employers have been increasingly vocal in their push for greater diversity, equity and inclusion over the last few years. Three-quarters of 5,000 respondents surveyed by PwC in 2021 said diversity and inclusion was a value or priority area for their organization. It's not just employers craving change; a 2021 report from CNBC and SurveyMonkey revealed 80% of respondents wanted to work for a company that values diversity, equity and inclusion.

As employers publicize efforts to create more diverse and inclusive organizations, some reports of unfairness have been made. Late last year, for example, a former AT&T assistant vice president who was an older, White male claimed he was ousted due to the company's commitment to diversify its leadership. According to his complaint, his termination violated the Age Discrimination in Employment Act as well as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The case is still in litigation.

In another, similar case from late last year, a jury found in a plaintiff's favor — resulting in a $10 million award. That plaintiff, also a White male, also used Title VII of the Civil Rights Act in his defense, noting his employer's stated diversity goals.

The cases prompt the question: When can DEI policies clash with anti-discrimination laws?

No 'huge influx' of reverse discrimination claims

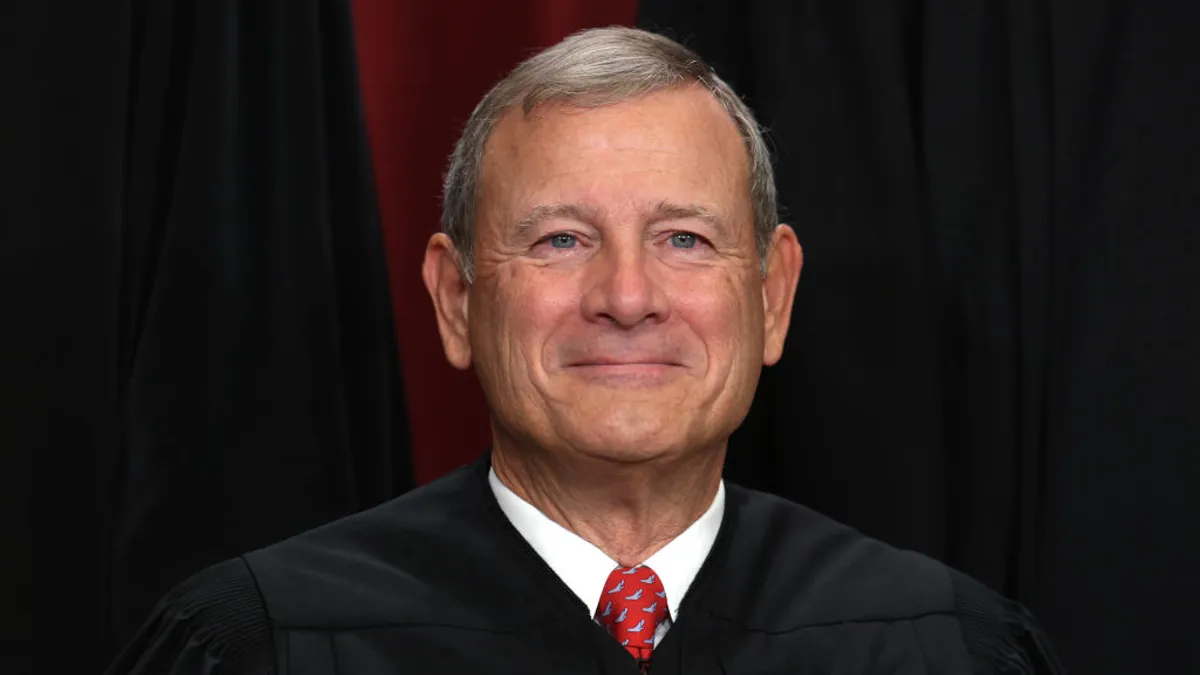

To delve into this topic, HR Dive spoke with Constangy Brooks, Smith & Prophete Partner Cara Crotty, who chairs her practice's affirmative action and OFCCP compliance group. She also serves on her firm's diversity, equity and inclusion committee.

"There have been a few incidents where employees have pushed back over DEI initiatives they think have gone too far," she noted, referencing a few examples. In 2018, for instance, a former recruiter for Google and YouTube alleged the companies retaliated against him after he complained about YouTube's hiring policies that allegedly prioritized certain minority applicants. Google was the subject of another 2018 lawsuit from a White male alleging race and sex discrimination. This time, it was filed by James Damore — the engineer Google fired for publishing a document suggesting women were naturally less inclined toward technology and criticizing Google's diversity policies.

The Trump administration also questioned diversity policies, Crotty noted. In September 2020, a memo from the White House Office of Management and Budget terminated federal agencies' diversity training that included critical race theory or referred to white privilege. Biden revoked that order within days of his inauguration.

Just after President Trump's order against diversity training, the U.S. Department of Labor's Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs questioned Microsoft's commitment to increase Black leadership without engaging in race discrimination. The agency sent similar questions to Wells Fargo.

On the whole, however, "there hasn't been a huge influx" of claims asserting DEI measures infringed on anti-discrimination laws, Crotty said. "Reverse discrimination claims have made [up] only a small portion of discrimination litigation."

Avoid unintended consequences

Even though U.S. employers haven't been besieged by discrimination claims regarding their DEI policies, employers need to work carefully as they seek to build or change DEI policies, Crotty said. Her first piece of advice? Involve counsel.

"It is really tricky," she said. "I've found that the very best intention can create unintended consequences."

To test a policy in development for potential problems, Crotty said employers can use her "back-of-the-napkin" approach. "Just reverse the language," she said. If an employer wants to require that its final-interview candidates include two minorities, it can consider how the policy would be perceived if it required its candidates to include two non-minorities.

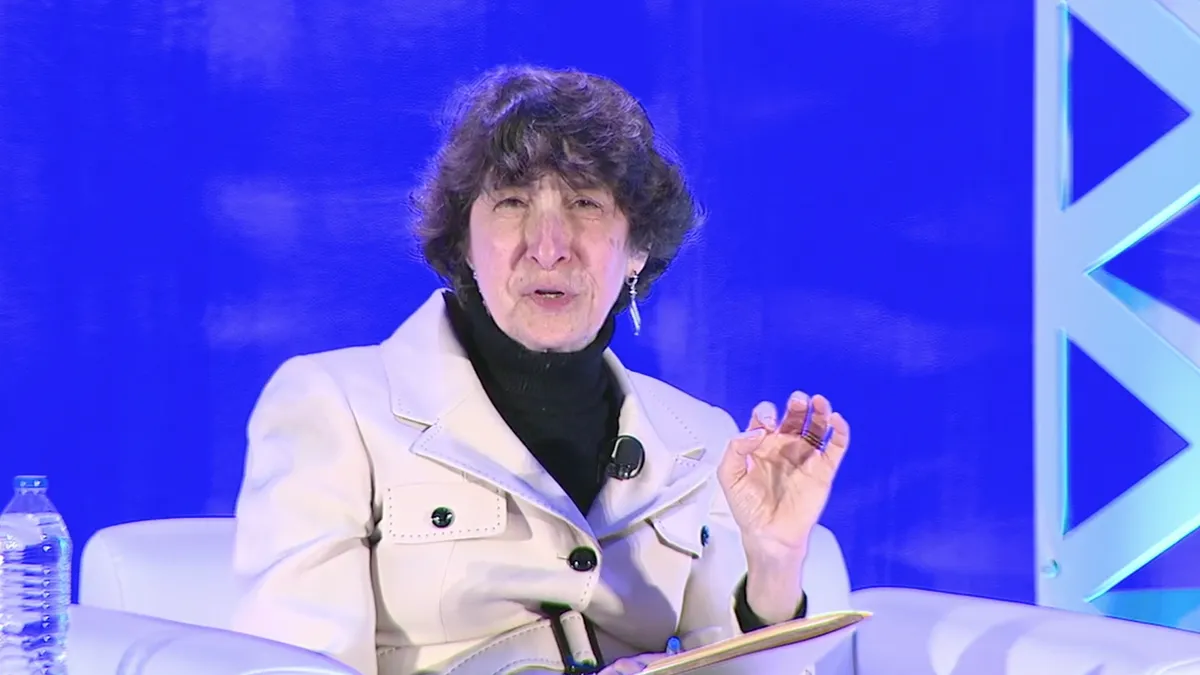

Chandran Fernando, a managing partner of Toronto-based Matrix360 — a self-described boutique talent management firm focused on DEI — also emphasized legal boundaries.

"Leaders who are responsible for the creation of workplace policies must participate in mandatory applicable employment equity opportunities and nondiscrimination legal principles and expectations," he said in an email interview. He recommended employers center all policies on human rights laws and "any other legislation that protects the welfare of all people."

He also encouraged DEI leaders to involve the widest breadth of people in discussions about policies and practices — including those who belong to the majority. "Do not forget about the White, heterosexual, able-bodied males," he said. "They too must be invited and welcomed to the table. Equity is about all people."

Affirmative action versus preference

Some areas of employment lend themselves more easily to DEI policies than others. Diversity initiatives that don't involve employment decisions — recruiting, for instance — won't create an outsized amount of potential for legal action.

For instance, there's a growing practice among employers to state in job posts that they encourage minority candidates to apply. "The statement in the job ad itself is not problematic," Crotty said. "Trying to recruit a diverse pool of candidates shouldn't be a problem."

In fact, Crotty noted, that's what the concept of affirmative action for federal contractors is based on. "They're required to cast a wide net. And the theory is that as they cast that wide net, their employee makeup will gradually reflect that of the candidate pool."

Still, there's a difference between affirmative action and preference. Employers should not state a preference for any kind of protected characteristic, like race, sex or ability, Crotty said. And employers should be aware that people who do take issue with their DEI policies could use an affirmative action policy as evidence to try and create an inference. "But it would just be one piece," Crotty said.