Title VII of the Civil Rights Act became law 60 years ago, on July 2, 1964. The statute was a landmark piece of legislation that protected workers from discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin — and it remains an active area of employment law today.

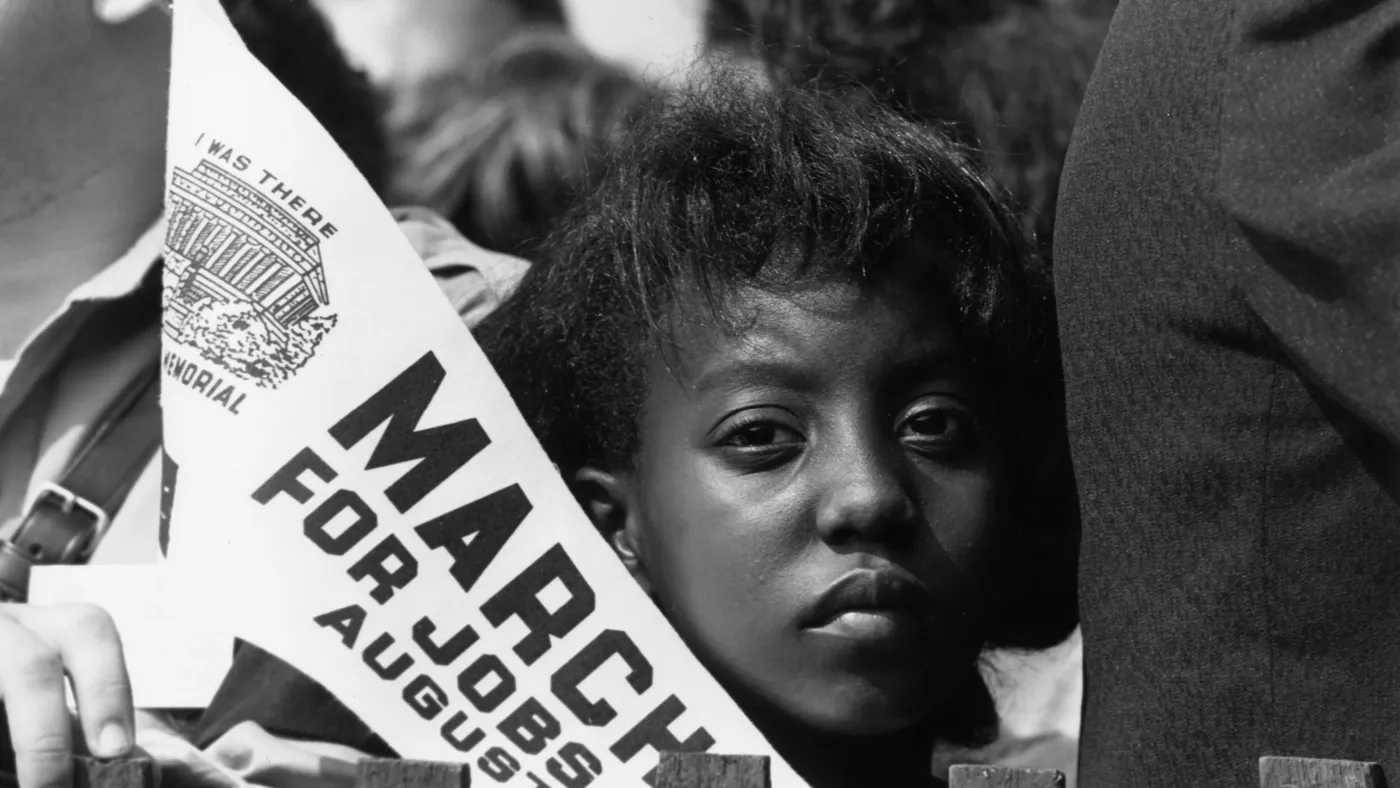

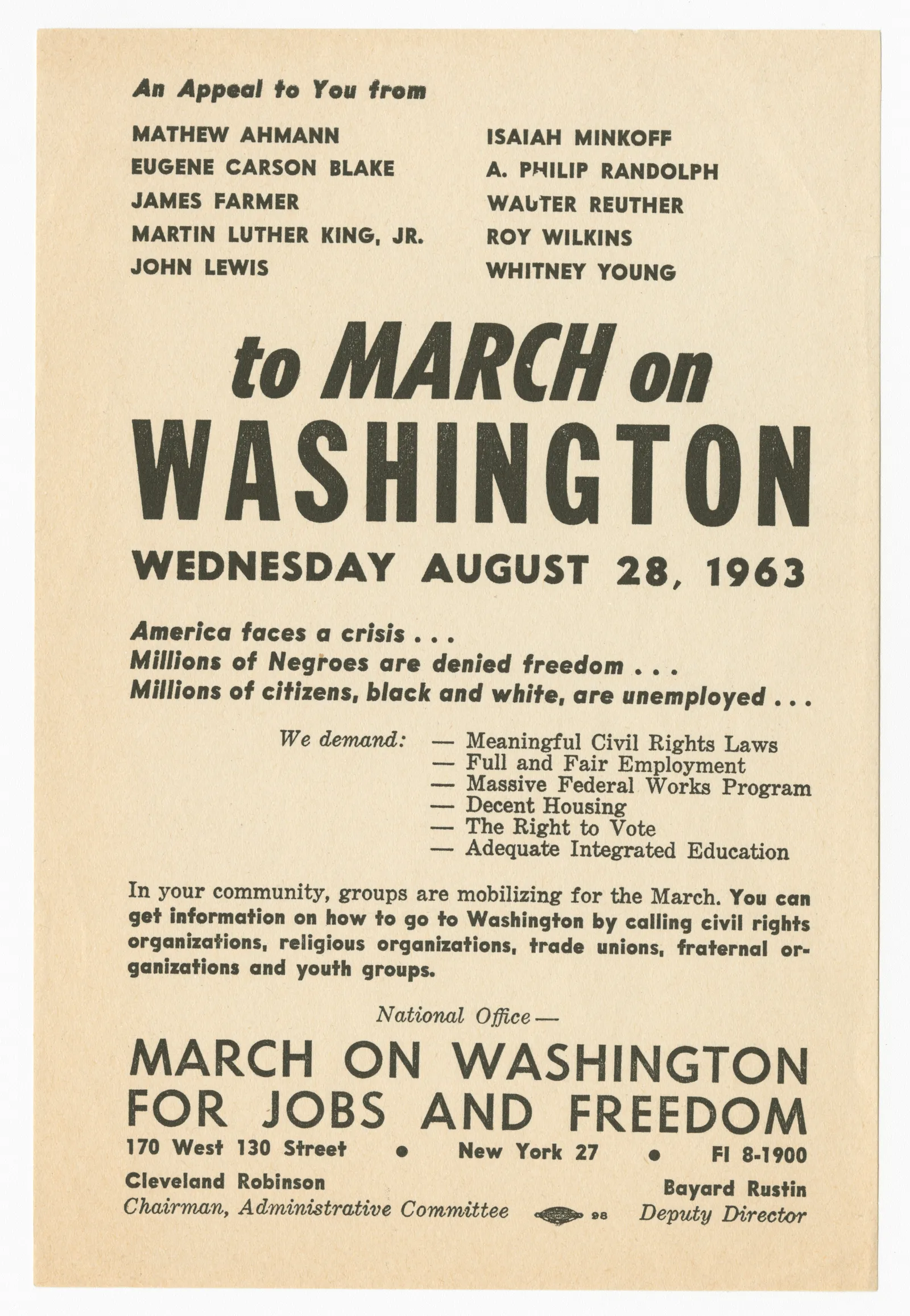

A myriad of advocates and movements were pushing for such legislation, but the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, held Aug. 28, 1963, proved a turning point for job protections.

That day, approximately 250,000 Americans marched for racial equality and justice, making it the country’s largest protest for racial justice to that point, according to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Attendees assembled in front of the Lincoln Memorial to hear speakers, including Martin Luther King Jr., who gave his historic "I Have a Dream" speech.

When the bill made its way to Congress, it likewise set a national record for longest debate. After 534 hours — and roughly 500 amendments — the Senate voted to pass the bill 73-27, according to EEOC history. Thirteen days later, the House did the same and sent the legislation to President Lyndon B. Johnson. He signed the bill into law the same day — with King right next to him.

In addition to creating nondiscrimination rights, Title VII created the EEOC to enforce those rights. The agency opened a year after the bill’s signing, July 2, 1965, with a budget of $2.25 million and about 100 employees.

The act established EEOC as a five-member group of commissioners, of which no more than three can be of the same political party. Each member is appointed to a five-year term by the president and confirmed by the Senate; the agency’s chairman was to appoint its general counsel, according to the commission. Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr. served as EEOC’s first chair, with Richard Graham, Aileen Hernandez, Samuel C. Jackson and Luther Holcomb rounding out the commission.

In its first year, EEOC expected to receive 2,000 charges, but the agency fielded 8,852 and developed a backlog. “We had thousands of charges even on day one. It has been a problem that we have been wrestling with from the beginning,” EEOC Chair Charlotte Burrows told Federal News Network as the law’s anniversary approached. That problem has continued throughout the agency’s history, with lawmakers pushing the commission to make headway on its backlog.

The commission today faces a hiring freeze and serious challenges to its policy positions. Eighteen states, for example, have filed a lawsuit alleging recently released harassment guidance unlawfully expands Title VII.

Title VII enforcement authority doesn’t sit exclusively with EEOC, however. On Sept. 24, 1965, Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, which established nondiscrimination employment standards for federal contractors.

Under the agreement, EEOC and the U.S. Department of Labor must coordinate on investigations of government contractors and, when EEOC identifies a Title VII violation but can’t secure an agreement, it refers the case to DOL for an enforcement action under the executive order.

Title VII would see a few substantive amendments during the decades that followed. After operating for years without litigation authority, Congress passed the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972.

The act gave EEOC the authority to litigate; made educational institutions, as well as local and state governments and the federal government, subject to Title VII; further reduced the number of employees an employer needed to have to be covered by Title VII from 25 to 15; and extended the period of time charging parties have to file charges. The amendments also gave the president, not the EEOC’s chairman, the authority to choose the agency’s general counsel.

Further legislation over the years clarified what types of discrimination are covered by Title VII, settling debates over interpretation of the law.

The Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 amended Title VII by explicitly stating that discrimination based on pregnancy or related medical conditions is considered sex discrimination.

And the Civil Rights Act of 1991, signed into law on Nov. 21, 1991, by President George H. W. Bush, amended Title VII — along with the Age Discrimination in Employment Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act — to allow parties to request jury trials and to recover compensatory and punitive damages in employment discrimination cases. The act also expanded Title VII to cover congressional and high-ranking political appointees.

President Barack Obama then signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 into law on Jan. 29, 2009, overturning the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., Inc. The act amended Title VII to say that every paycheck involving discriminatory compensation is a separate violation, despite when the discrimination began.

In addition to Ledbetter, a number of Supreme Court rulings have reshaped the Title VII landscape over the years.

In one of its more recent landmark rulings, the high court held on June 15, 2020, that employment discrimination based on a worker’s sexual orientation or gender identity is not permitted under Title VII. Prior to the decision, federal courts and agencies had debated if Title VII prohibited LGBTQ+ discrimination.

That case, Bostock v. Clayton County, Ga., cemented additional protections for workers and is one of several recent rulings stakeholders expect to shape the future of Title VII, along with two others.

In Groff v. DeJoy, a unanimous court struck down the “more than a de minimis cost” standard for determining whether a proposed workplace accommodation for an employee’s sincerely held religious belief or practice poses undue hardship. And in Muldrow v. City of St. Louis, the court held that employees challenging a job transfer need not show that the transfer caused “significant” harm.

At the same time, the federal government has shared concerns about how emerging technology — namely, artificial intelligence — could impede Title VII and its protections. The White House has made clear it will focus on how AI could perpetuate bias and has called on federal enforcement officials to step up. EEOC has already cautioned employers that they’ll be held responsible for any Title VII violations created by any technology implemented in the workplace.

At 60 years old, Title VII remains a core tenet of employment law and a cornerstone in how discrimination in the workplace is resolved. The statute has seen many changes during its time in the books and, according to at least one EEOC official, will continue to see developments as society shifts and technology evolves.