Editor’s note: In this column, Reporter Ryan Golden discusses his takeaways after attending a series of thought-provoking artificial intelligence sessions at SHRM Inclusion 2023.

It’s 2025. We no longer toil away at our desks, goaded by tiny red dots on an envelope icon to mark endless streams of messages as “read”. There are no more meetings. The office Keurigs not already confined to dumpsters have gathered visible dust. These are the scenes of a world where knowledge work is exclusively the domain of artificial intelligence.

OK, that’s not how the next year and a half will shake out. Probably. But to deny the inroads AI has made within and without the HR profession is to deny reality.

Of course, we can’t talk about AI without talking about ChatGPT, the OpenAI-developed chatbot that can whip up compositions in seconds with just a simple prompt. I saw ChatGPT’s HR applications firsthand at the Society for Human Resource Management’s Inclusion conference last week in Savannah, Georgia.

The ChatGPT crash course

At a Halloween afternoon session, Carol A. Kiburz, a member of SHRM’s Speakers Bureau and industry veteran, said she has used ChatGPT to write all manner of documents, including job postings, employee handbooks, offer letters, employment contracts and even collective bargaining agreements. For any piece of HR paperwork you can think of, ChatGPT can tailor it to your specifications, Kiburz said.

What Kiburz generated was admittedly impressive. The chatbot crafted job titles with specific requirements and duties for a senior electrical engineer at a small electric company operating only in the U.S. She successfully prompted ChatGPT to generate a Spanish-language employee assistance program access guide using a prompt written in English.

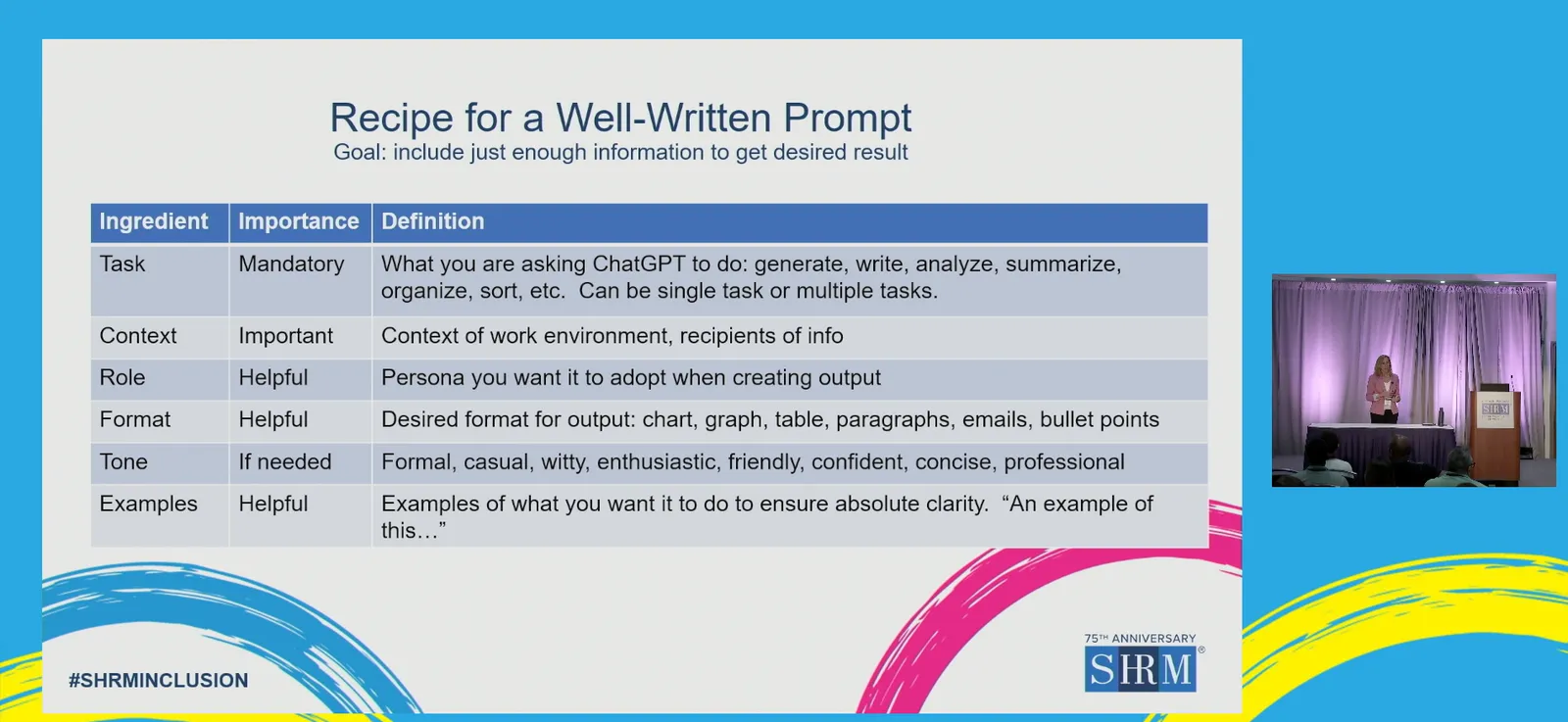

Yet, for the time being, HR professionals can’t expect ChatGPT to come up with flawless versions of these documents. As Kiburz demonstrated, users will still need to craft the correct prompts — typically a few sentences long — to get as close as possible to what they want.

“Think of it this way, there’s some rules of thumb: garbage in, garbage out,” Kiburz said. “What you give [ChatGPT] is really important. The more specific, the better.”

HR professionals also must check AI-produced content for the basics, from accuracy to grammar and punctuation to overall consistency with the employer’s brand, Kiburz continued. Some passages may be duplicated, and it’s possible for AI to make up information entirely.

Moreover, employers will want to constrain the information they feed to ChatGPT so that they do not provide any sensitive details, Kiburz said.

For me, but not for thee?

That Kiburz seemed so open about AI’s potential was striking given a separate session at SHRM Inclusion that I attended just hours prior. Kelly Dobbs Bunting, shareholder at Greenberg Traurig, had wrapped up her presentation on state, local and federal regulation of AI in HR and began taking audience questions. I found one question to be of particular interest.

“We love a strong cover letter,” said an attendee, who did not identify which employer they represented. “We look at all of them. Are we allowed to put some guidance around asking people not to use AI to help them with their cover letter?”

The attendee continued, “If we suspect that someone has used AI to help them draft their cover letter, can we engage them about that?”

It’s a fair question and one that many recruiters probably have in this early stage of AI. But after listening to Kiburz’s presentation and seeing how valuable an asset the technology can be for HR practitioners, I have to ask: How can an employer justify asking candidates not to use ChatGPT to write a cover letter?

Cover letters, resumes are popular use cases for AI

Frankly, there seems to be little difference between a recruiter who uses ChatGPT to generate a draft job description — perhaps because they wish to save time for other tasks — and a job candidate who uses ChatGPT to generate a draft cover letter to save time for more intensive aspects of the application process, such as building their resume, contacting personal references or practicing interviews.

Moreover, how can employers be sure that job candidates who use AI to draft a cover letter are not also checking the AI’s work for grammar, spelling and accuracy, just as a recruiter would for an AI-generated job description? And why should HR assume that such a cover letter would not be “strong”?

The idea that candidates would not do their due diligence before submitting AI-generated content is downright cynical. Even parties that encourage job seekers to use AI-generated content advise using that content as “a source of inspiration and a starting point,” to borrow the phrasing of Australian recruitment agency Michael Page, and to review and customize it to reflect the candidate’s own experiences and ensure originality.

That’s not to say the SHRM attendee in question assumes AI will exclusively be used to churn out low-effort, cookie-cutter cover letters. The attendee also did not say that their company bans candidates who submit such cover letters, but instead asked whether the company could “engage” candidates about AI use to ensure honesty.

A different viewpoint

Regardless of their stance, employers will be seeing more and more job applications assisted by generative AI.

A recent Gartner survey of 3,500 job seekers found that nearly half, 46%, had used the technology during the application process within the past year, Gartner said in an email. Of those candidates that did use AI, 50% used it to create a cover letter, 49% for a resume or CV and 44% for a writing sample.

Should HR professionals find themselves interviewing a candidate who has used AI to help put forward an application, they might take the perspective of Alex Alonso, SHRM’s chief knowledge officer. In a thorough discussion on AI’s role in HR, Alonso encouraged attendees to look at employee and candidate use from a different lens.

“One of the things that happens is that a lot of employers have a knee-jerk reaction,” he said. “It’s a tool. I don’t know how many of you hire engineers, analysts or scientists, [but] if you want to get a much better letter and communication from them, you definitely want them using generative AI. You want them using these tools.”

Of course, there’s plenty of reasons for users on both sides to use caution. As Alonso and Kiburz noted, generative AI presents complex intellectual property questions. There are also concerns that AI tools used for screening and evaluating candidates may introduce or amplify bias in the hiring process.

Legitimate reservations aside, HR professionals will — and by many accounts, are — using AI to assist with often repetitive tasks in order to elevate their work. If we are to assume that most are doing so carefully and responsibly, it is more than reasonable to extend that same grace to job candidates.