From asking about potential symptoms to vaccination status, the share of employers collecting health information from their workforces has grown. The trend is drawing concerns from some management-side attorneys amid the reopening of physical workspaces.

A March survey by Littler Mendelson of 1,275 employer representatives found that 74% of respondents were either currently tracking or planning to track workers’ vaccination status. Even among respondents who did not have a vaccination policy in place, 54% said their organizations were tracking vaccination status.

But given intermingling local, state and federal requirements on health information privacy, it is important for employers to note that they “may not have done the most careful job” of collecting and storing such information, according to Devjani Mishra, shareholder at Littler.

In its analysis of the survey results, Littler said most respondents were using spreadsheets or other internal software, both of which, it noted, could raise data privacy issues.

Sources who spoke to HR Dive discussed the laws that apply to medical information collected as part of the reopening process and the best practices employers may take to complete such collections without running afoul of federal, state and local laws.

Which laws apply?

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, protects an individual’s medical and health plan records, but the law generally does not apply to employment records, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Health plans, insurers and related parties may disclose protected information to employers that sponsor and maintain a group health plan, but only under specific circumstances.

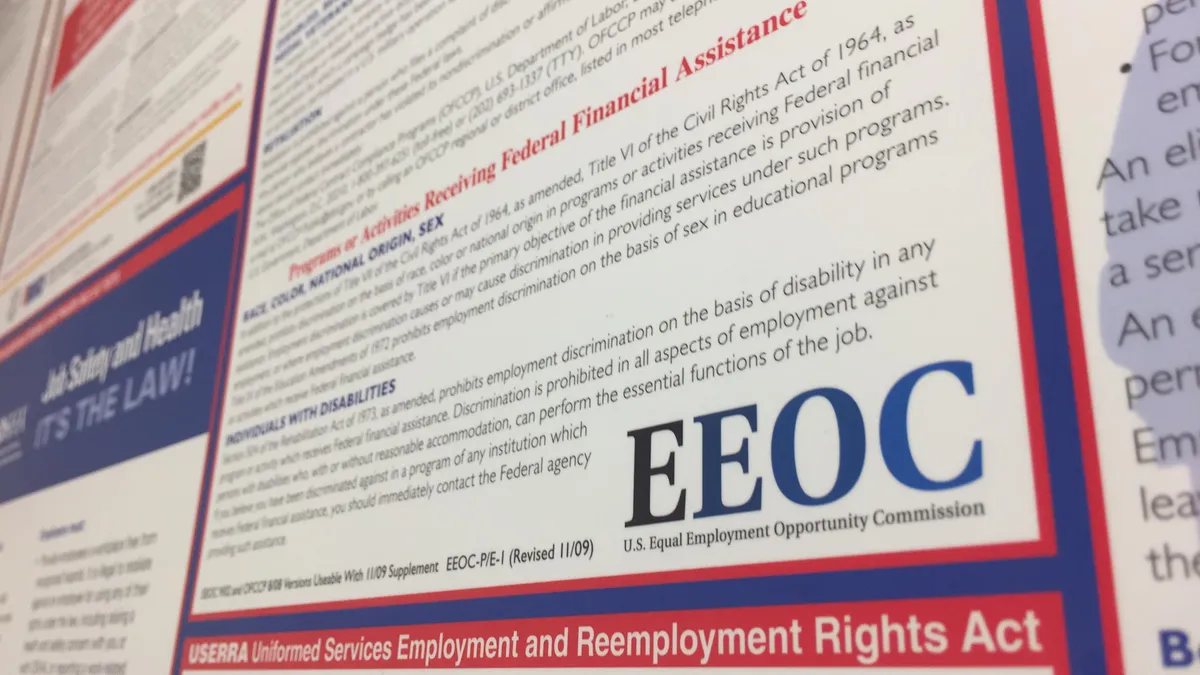

Instead, questions about how an employee is feeling or whether they are vaccinated are more likely to involve the Americans with Disabilities Act and various state and local laws, Mishra said.

For example, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission’s technical assistance document states that the ADA requires employers to store all medical information — including COVID-19-related items, such as the results of an employee’s temperature check or self-identified diagnosis of COVID-19 — in the employee’s medical file, separate from the employee’s personnel file.

That information also must be kept confidential under the ADA, per EEOC, but managers who are informed of an employee’s symptoms and diagnosis generally may report these details to the appropriate officials. Still, employers “should make every effort to limit the number of people who get to know the name of the employee,” the agency said.

Do vaccine questions count?

Vaccination status is similarly protected by the ADA. Employers may issue vaccination requirements and make a record of employees’ statuses under the law for safety purposes, but they still need to ensure that information is confidential, Mishra said.

Additionally, employers may not want to ask why an employee is unvaccinated if this information is not required, because “you’re sort of tripping into information you do not need,” Mishra said. “If you do [require it], you need to wall that in from other decisions involving the employee.”

Vaccine data collection also illustrates the compliance questions inherent in state and local information privacy laws. For example, California’s Consumer Privacy Act requires employers that collect personal information for employment purposes to provide a notice of collection to applicable workers describing the categories of information collected and the purposes for which the information will be used. California employers will see additional requirements under this law beginning in 2023.

Vaccination status could fall under the California law’s broad definition of personal information and may need to be included in the required collection notices, according to Joseph Lazzarotti, principal at Jackson Lewis and co-leader of the firm’s privacy, data and cybersecurity practice group. As with data privacy laws in other jurisdictions, California’s also requires businesses to implement reasonable security procedures and practices to safeguard personal information.

If employers use third party vendors or apps to track vaccination status, this may create other considerations. Lazzarotti said employers using such services will want to understand what types of safeguards vendors have, such as two-factor authentication and encryption, to protect employees’ data. If employees are downloading an application onto their devices to submit their information, Lazzarotti added that employers might want to have an understanding of what the app’s privacy statement looks like.

Due diligence is key when contracting with vendors, said Mishra, who noted that employers should ask how vendors are storing the data they collect, and whether vendors are selling that data. “The employer is going to bear the responsibility for setting up a situation [in which] the data intentionally or unintentionally is going somewhere it shouldn’t,” she continued.

Employers also may need to plan for what will happen to vaccine-related data beyond the collection period, given that this data would presumably still be stored on vendors’ systems. “When we no longer need to track it, how do we get it back or get the vendor to delete it?” Lazzarotti said.

The impact of long COVID-19

Officials at the EEOC and elsewhere have recently commented on long COVID-19 and the challenges the condition may present to workers. Long COVID-19 also challenges employers, because it encompasses a wide range of symptoms that can inhibit employees’ major life activities and therefore merit accommodation under the ADA.

Additionally, long COVID-19 may exacerbate existing health conditions that did not rise to the level of a disability in the past.

But applying health information privacy principles is not really much different from managing short or intermediate bouts with COVID-19, Mishra said. The core of those discussions between employees and disability management practitioners would be the same interactive process that guides how employers navigate other underlying conditions that affect a workers’ ability to perform a job.

“Don’t let the work of responding to COVID distract you from the good practices and the knowledge you already have,” Mishra said. Employers, she added, would still need to perform a fact-specific assessment of the employee’s job and analyze whether the employee is presenting a physical issue requiring some kind of change to the job.

Lazzarotti answered similarly; “I think you have to go back to the basics.” Employers who have staff that handle the interactive process should train these individuals on how to comply with the ADA and avoid sharing confidential information with supervisors or employees, he said.

Reopening may present an opportunity for employers to take a look at the bigger picture of their privacy and data security efforts, Lazzarotti continued. Employers keep a variety of employee data on hand even if they do not need every single piece of that data, but they may not always be following proper security procedures, such as encryption, he said. That can create unnecessary risk by itself.

“I think employers raise these things because of COVID, but sometimes you don’t about everyday privacy,” Lazzarotti said. “It’s a good opportunity to review the company’s practices and understand what kind of data you’re getting.”