In this Employee Experience column, HR Dive reporter Caroline Colvin acknowledges an oft-undiscussed part of the talent lifecycle: job candidacy. They discuss the trend of recruiter ghosting and interview a worker who has been ghosted throughout their yearlong job search.

Anyone who has searched for a job in the past few years knows it takes a colossal effort.

Recent developments, like New York City’s transparency law taking effect, have made some aspects of the job search more candid. But there’s also more dishonesty or a lack of communication — leaving many workers to feel like their time has been wasted. Many, if not most, job seekers get ghosted by employers. Almost 80% of job seekers reported as much to Indeed in a 2021 survey.

Other stats show that 80% of job candidates on average want faster response times from recruiters, per HCM platform Sense’s 2022 study. Candidates also want better overall job search experiences, Sense reported.

I’ve found that these grievances continue to creep up across social media.

Recently, I came across an earnest LinkedIn post from a former Syracuse University classmate discussing the discouragement of getting ghosted professionally. Cherokee Hubbert has been working since she was 18 years old, but has built a career in public relations and social media since college. She’s had internships, she has freelanced and she has worked full-time jobs.

Cherokee told me that while looking for a new job — she’s looking to parlay her experiences into creative strategy and project management, and has been searching for a little more than a year — she has completed 40 interviews.

“The longest interview process I've had was a total of two months, including 12 rounds of interviews with three different teams, a rescinded offer due to role elimination and three projects,” she told HR Dive via email.

A dream deferred: LinkedIn edition

Generally speaking, getting ghosted isn’t a pleasant feeling, she acknowledged. “But my worst experience was after I submitted a presentation that I was extremely proud of completing, for a sports and entertainment agency. It was the perfect role as a senior manager on their brand experiences team.”

Hubbert met with a recruiter and hiring manager who ‘enjoyed [their] conversation enough to send [her] to the next round,” which was a second project.

“I wasn't thrilled about doing another project, but it was an exciting topic so I completed the project two days ahead of the deadline. Once I shared the project, I was told that the hiring manager was out of town and that my project would be shared for review by another member of the team,” Cherokee said. “Unfortunately, after following up, I never heard from that company again. I even applied for another position within the company, hoping for a better outcome, but my application never received a response.”

What happens to a dream deferred? / Does it dry up / like a raisin in the sun? / Or fester like a sore— / And then run?

Langston Hughes, “Harlem”

This led Cherokee to expel her frustrations on LinkedIn. She wrote, “The job search is challenging enough without recruiters who ghost after they’ve painted a dream of their company and reached out to you with the perfect role for your next move.” In her post, she challenged the idea of fitting into a mold for “a generic job posting.” She also spoke about being “haunted” by gaps in her work history.

The ghosting experience made her feel “invisible,” “inexperienced” and “lazy.” She wondered aloud if recruiters ever consider that people step away from work to shoulder caregiving responsibilities, write books or take care of their mental health.

Why recruiters ghost candidates

There will only be one person who knows why they ghosted a potential hire, and that person is unreachable for communications. I’ve found anecdotally — through Indeed and social media — recruiters have given a few excuses:

- The company in question is no longer hiring for that role.

- A potential hire’s salary expectations exceed the budget.

- The role is deeply competitive.

- “Internal obstacles,” as in: some hiccup has occurred between the agency recruiter and the employer.

Another option that the Indeed blog post raises: simply, personal developments.

“Recruiters can have the same shortcomings as any other individual. They might not respond to your email or requests for more information because they’re on vacation or are experiencing a family emergency, a health concern or some other unforeseen circumstance,” Indeed said. “While some recruiters are honest about potential delays, they may not always offer you this courtesy, especially if they’re already busy.”

Arguably, Cherokee had already mulled over these possibilities by the time we spoke for our interview.

“Throughout my job search, I’ve learned that companies do not take chances on what I like to call ‘gray area hires’ — those hires are people who have a variety of skill sets that do not seem to fit,” she said. “But that doesn’t mean that they can’t be the right person for the job.”

Hiring for potential or “skills-based hiring” has gained traction in recent years, with the public sector taking the lead in this hiring trend. The state of Maryland dropped its four-year degree requirement for thousands of jobs in 2022. Pennsylvania followed suit the next year; now 90% of state jobs will no longer require a four-year degree, according to Gov. Josh Shapiro, D-Penn.

Still, labor experts have suggested employers are still overlooking “nontraditional” candidates.

Regarding nontraditional candidates, Cherokee added, “Sometimes it means that the role can transform to meet the experience of the hire if they are a great match for the company — while bringing something special to the table.”

She also noted that often, companies have preselected their job candidate “whether it’s how they look, their mutual connections, where they went to school, their years of experience or where they’ve worked before,” she said.

How recruiters can make the candidate experience better

HR professional Scott Sparks also wrote a LinkedIn post about recruiter ghosting, from the point of view of someone who has worked in talent acquisition before. He called the trend “unsettling,” noting that he had spoken with “dozens of colleagues” who have been ghosting victims.

Echoing Cherokee’s sentiments, he noted the real harm that ghosting can cause workers.

“After investing time and effort into crafting tailored resumes and cover letters, preparing for interviews, and building hope, being met with sudden silence from a recruiter can be deeply discouraging,” he said. “The lack of closure and feedback can lead to feelings of rejection, self-doubt, and frustration, damaging the job seeker’s overall confidence and well-being.”

Beyond following up on their own, Scott recommended that job seekers be candid about their experiences with recruiters, “highlighting those who prioritize respectful communication.”

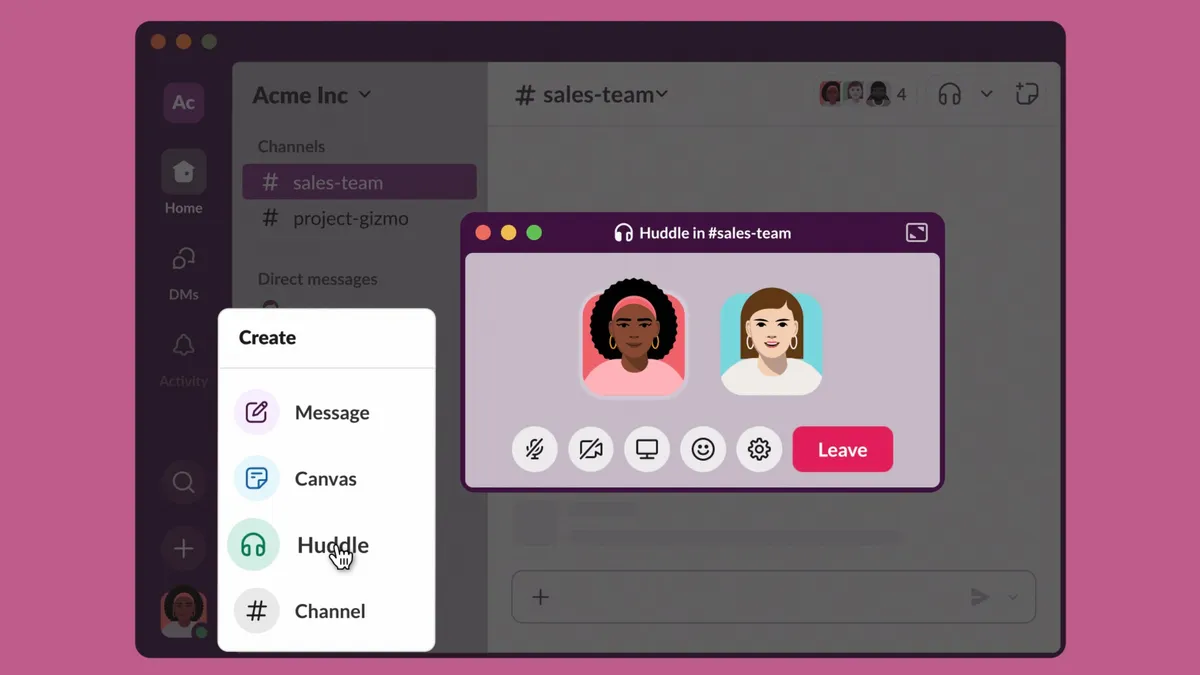

His solution for HR? Recruiters can outline the steps of the hiring process and projected timelines, to get candidates on the same page. Hiring managers can “regularly update candidates on their application status, and promptly respond to candidate inquiries.”

Cherokee hoped that more talent acquisition professionals would do the same.

“It’s as simple as an email. A call. Something that will show the candidate that you appreciate the time they spent in the interview process or on an application,” she said, noting a more positive experience with a PR firm. Even though two teams at this company ultimately rejected her, Cherokee was kept up to date at every step of the process by her point of contact.

“[That hiring manager] was attentive and cared about the amount of time and effort I put into every task,” Cherokee said.