Editor’s Note: This story is the first in a series about employers reaching out to nontraditional workforces.

Jabarre Jarrett was worried every day once he got out of prison.

With a felony on his record, he didn’t know how he would provide for the five children he and his fiancee share. He knew getting a job would be tough.

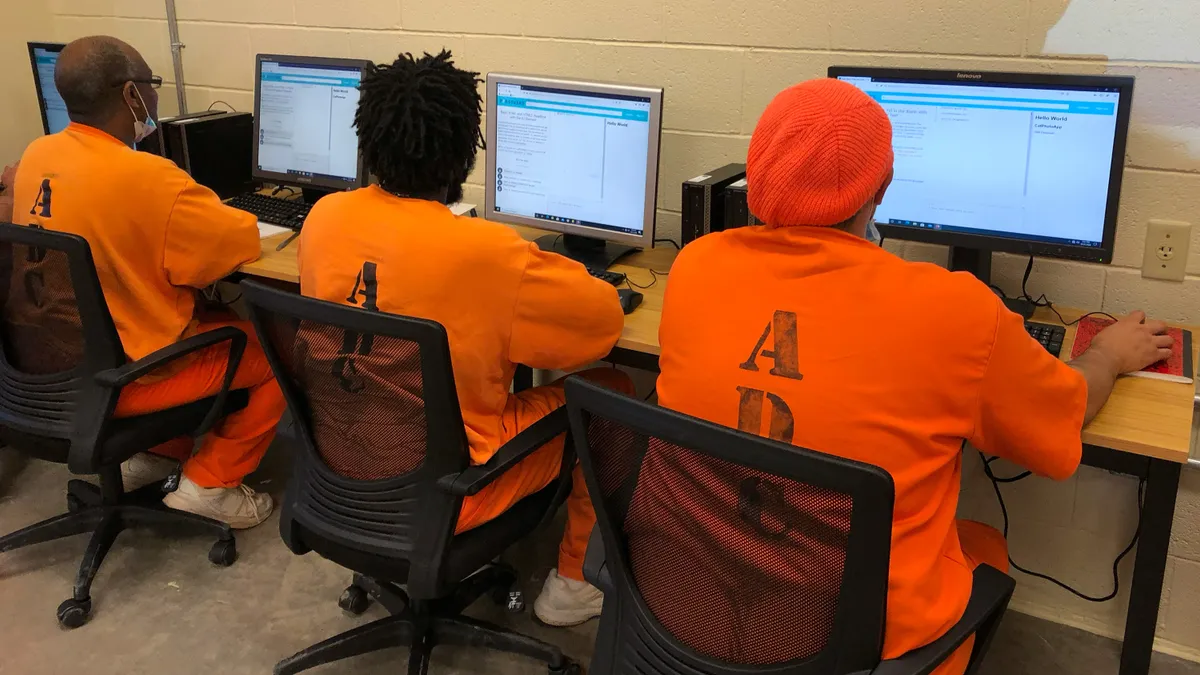

At a halfway house in Jackson, Tennessee, Jarrett learned about Persevere, a not-for-profit organization that provides those who have been incarcerated with engineering and coding training both inside and outside of the prison walls.

Every Monday, residents at the house would sit in a huddle around the phone and listen to a recording sharing job opportunities. Persevere offered enrollees a free laptop and a $1,000 stipend if they completed the program, Jarrett said.

“It was our responsibility to jot down what benefits you,” Jarrett said.

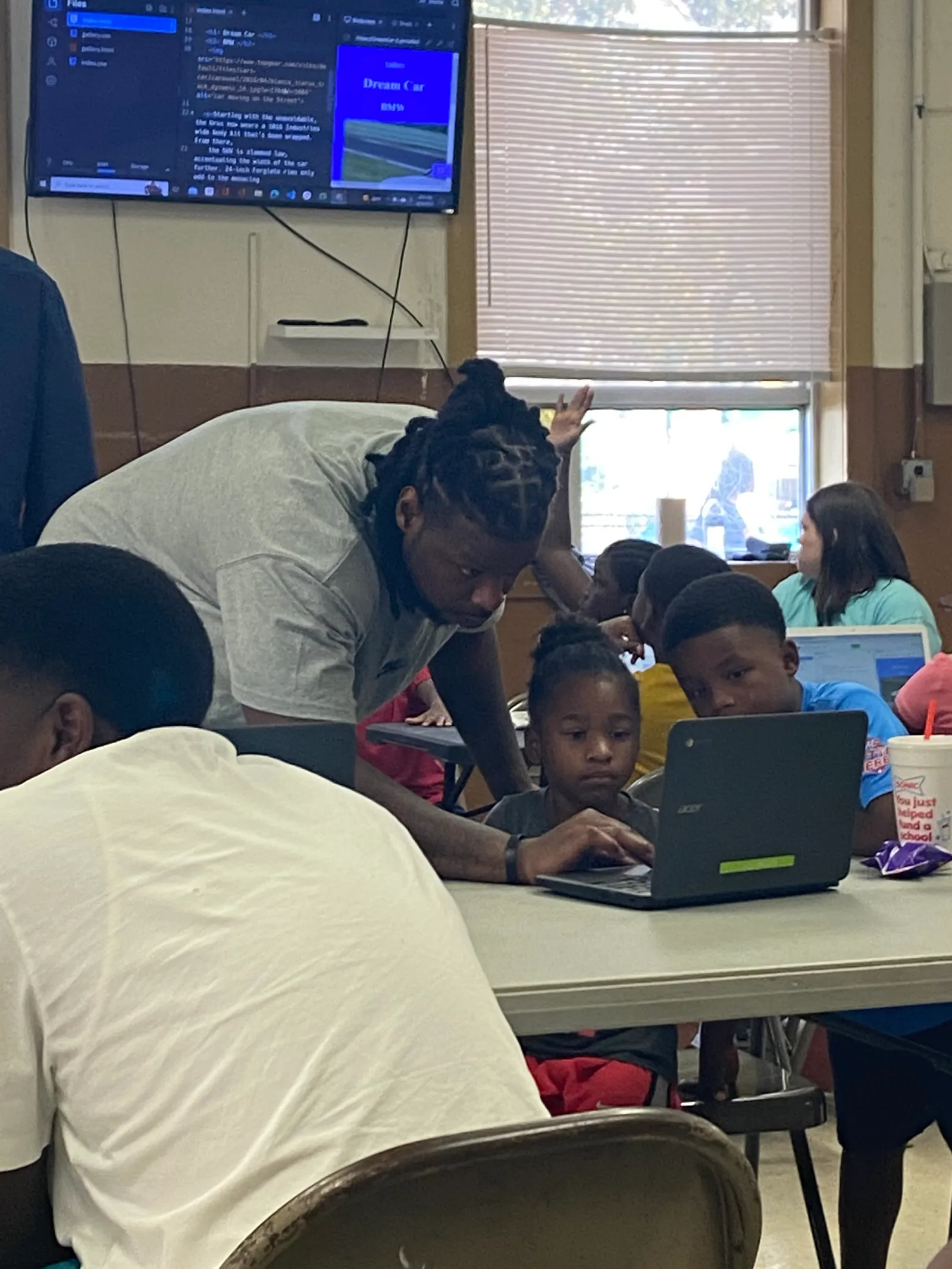

Two months after he was released from prison, Jarrett started the program, alongside his daughter — part of Persevere’s effort to help families who have been involved in the criminal justice system. In the first six months, he earned a front-end developer certification and, in the second, a back-end certification, making him a full-stack web developer.

Formerly incarcerated people have an unemployment rate of more than 27%, the Prison Policy Initiative, a research and advocacy organization, found. Nearly half (46%) of unemployed men in the U.S. have been convicted of a crime, a February 2022 report by The RAND Corp. said.

At the end of his program with Persevere, Jarrett was hired on a temporary basis to help the company with a grant. By the end, Persevere decided to hire him.

“I was so excited about the opportunity that I took full advantage of it,” Jarrett said. “I tried my best to leave a good impression on them, and it paid off.”

He started out instructing youth on web development and now teaches life skills. He goes inside juvenile facilities and speaks with children, visits state prisons to talk with those behind bars and has been a speaker at a high school. He hopes to get a degree specializing in mental health.

“It's the greatest feeling in the world just to be able to be the one to say, ‘Just look at me. I felt just like you felt, and I overcame it,’” Jarrett said. “It makes me want to keep going every day knowing I’m helping somebody change their life.”

For employers, second-chance hiring can be a chance to tap into a new talent pool, to improve diversity and inclusion efforts and to possibly earn a tax credit. For those with a conviction in their past, fair-chance hiring is a fresh start.

“I love what I do,” Jarrett said. “Every day you’re blessed with a new opportunity and what you make of it.”

A second chance

Across the U.S., businesses are teaming up with organizations like Persevere to implement hiring programs inclusive of people with convictions. The Second Chance Business Coalition, a group of large private-sector companies, including JPMorgan Chase and Eaton, now has more than 40 members working together to promote second-chance hiring.

And at least 37 states and 150 cities and counties have ban-the-box laws in place, per the National Employment Law Project, a worker advocacy organization. These laws prevent employers from asking about arrest and conviction records on job applications, pushing criminal background checks later in the hiring process.

On an application that has a box to check if you’ve committed a felony, “if you check that box, they file it in the trash,” said Tony Lowden, vice president of reintegration and community engagement at ViaPath, which supplies tablets to prisons for online educational and vocational training. “We don’t give individuals an opportunity to interview for positions.”

Instead, companies need to hire individuals who were incarcerated, mentor them and help them stay in the workforce, said Lowden, who is the former executive director of the White House’s Federal Interagency Council on Crime Prevention and Improving Reentry, a multiagency council designed to reduce crime and create better outcomes for those who have been incarcerated.

“Having a felony on your record should not put you and our family in a lifetime of poverty,” Lowden said. “When a person comes home, if we want our communities to be healthier and safer, we should give individuals an opportunity to get a job.”

In the U.S., 62% of people who were released from prison in 34 states in 2012 were arrested again within three years, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. That number climbs to 71% five years after release. An older report that followed 6,500 formerly incarcerated individuals for five years after their release from the Indiana Department of Correction found that employment status was one of the biggest predictors of recidivism, or reoffending.

Despite gains in fair-chance hiring, there’s still work to be done, said Anthony Glover, employment coordinator at Persevere. Ban-the-box laws “just moved the box from the front of the application to the back,” he said. Employers can still request a criminal background check once they’ve made a contingent offer.

Persevere pairs enrollees in its job training programs with wraparound services like case management, transitional housing and mental health counseling, and it continues to offer its graduates support for a year after they finish the program, Glover said.

“Just like any other employee, if your life is in disarray, how productive are you really going to be?” Glover said. “We try to make sure our graduates have the support they need so they have someone to lean on when they have to.”

Companies that want to create a culture where formerly incarcerated individuals can succeed offer apprenticeships, internships and mentorships, Glover said. They’re getting leadership on board, working with departments of corrections and providing training and support, he said.

“We’re finding there are companies that are stepping up to build a more diverse workforce,” Glover said.